I often conduct research alone in libraries and archives. For example, a recent project investigated at the Nubar Library in Paris led to the 2023 publication of my book, Outcasting Armenians: Tanzimat of the Provinces. However, one project I am currently working on involves collaboration with a small team—students turned friends turned collaborators—who are interested in understanding their family histories.

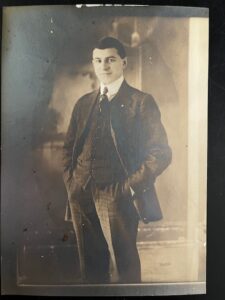

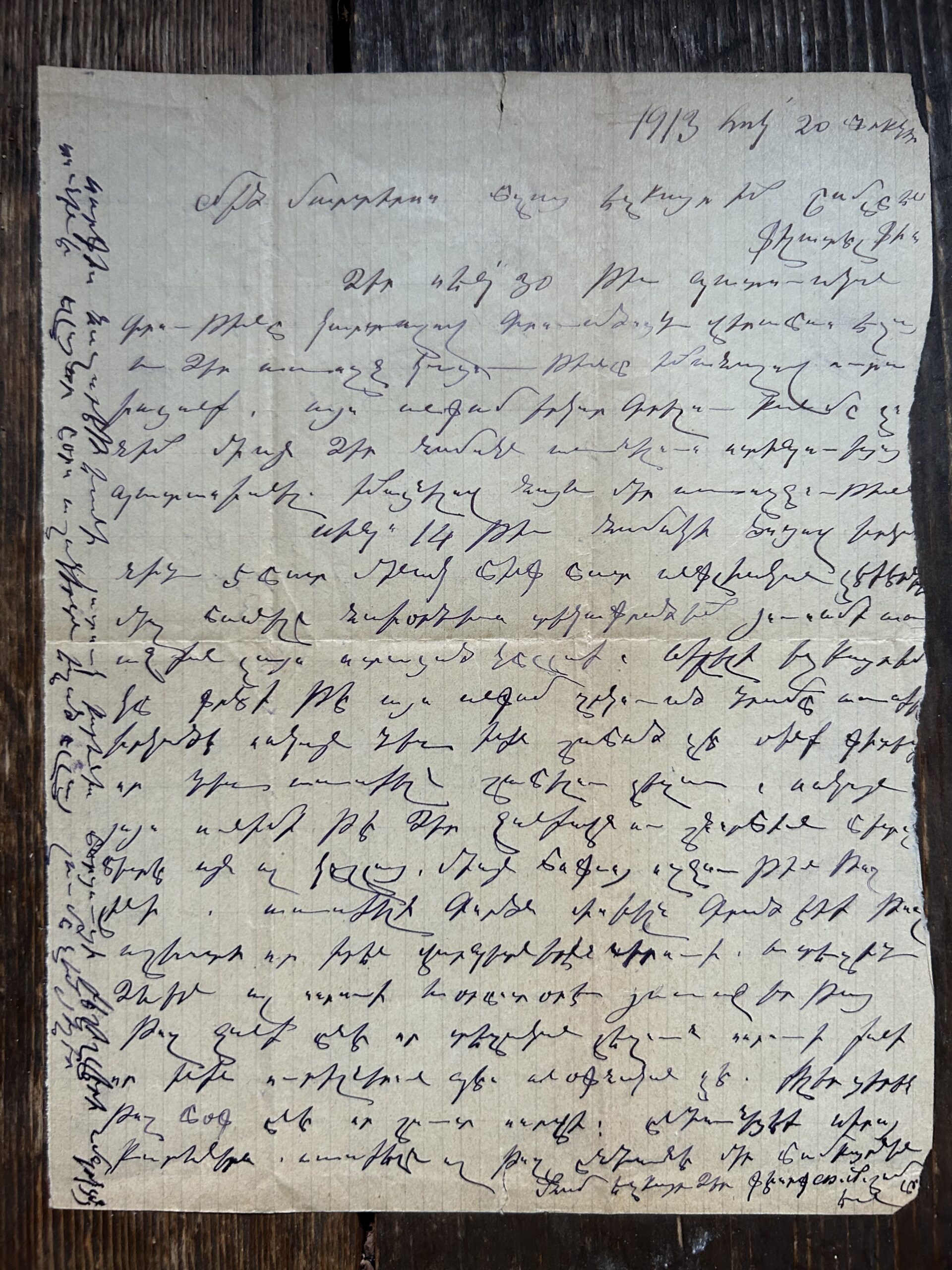

Our endeavor here concerns a set of letters written from Arapgir to Philadelphia beginning in 1913. The correspondence is primarily between Kevork Shamlian in Arapgir and his younger brother Mardiros, as well as Kevork and his 19-year-old son Arakel. Both Mardiros and Arakel migrated to Philadelphia as bantukhds, or migrant workers, due to the untenable conditions for young men in the Ottoman Empire. These letters reveal many things: the conditions of Armenians in the provinces of the Empire, the anxiety of a father sending his son away for his own safety, the hopes that things would improve for all—and the fears that they would not.

The letters span from 1913 through 1914, with three additional letters from 1915. It is through Kevork, writing from Arapgir, that we learn so much—about the close relationships within Armenian families of the provinces, the sophisticated levels of literacy among Armenians and the hardships that foreshadow the disaster to come. As the head of a large family, Kevork’s letters illuminate his fatherly devotion and deep faith in God. Most likely sensing the impending catastrophe, he nevertheless continually reassures his son Arakel, as well as his own brother Mardiros, that those left behind in the Ottoman lands are fine.

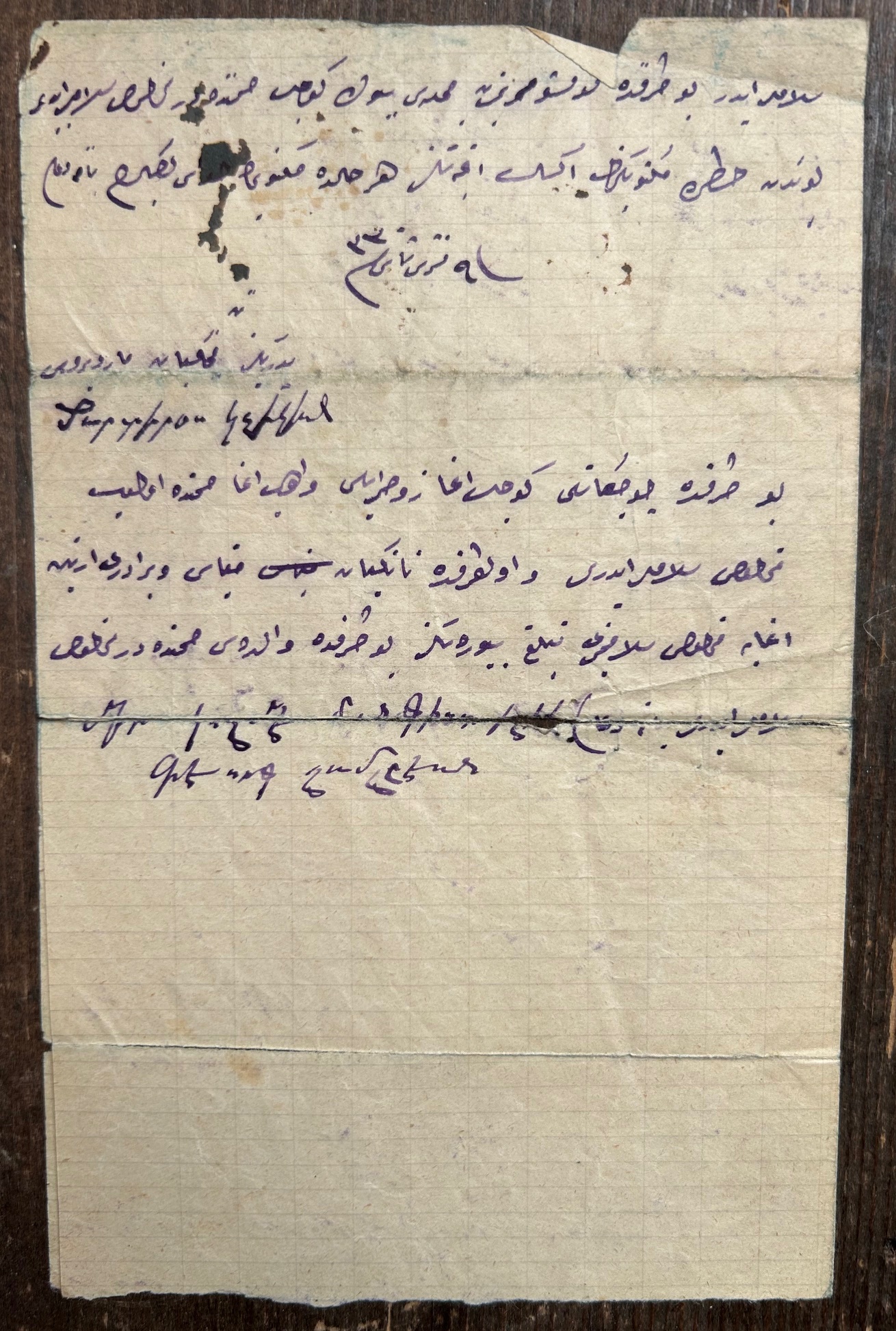

However, the first letter I read presented quite a mystery. Two things were unusual about this letter: it was dated with the Rumi calendar, and it was written in Ottoman Turkish script by a Shamlian relative, Mardiros Gchigyan. Only the postscript was written by Kevork Shamlian, and this was in Armenian. I read each line with anticipation, hoping to find more than just greetings from all the family members to loved ones in America. It seemed as if all those named were “fine” in this time of turmoil and were sending their “special greetings” to relatives in Philadelphia.

Here is the English translation of that letter:

To my son Artin and Arakel Agha,

With my special greetings, I hope you’re doing fine. If you ask us, until the date of this letter, we are all safe and sound and we greet you specially. We were very happy to receive a number of letters from you, which we read longingly. Your mother…and brother Minas Agha and your daughter are healthy; they send their greetings. Your brother-in-law Haji Kevork Agha is healthy and he sends his greetings. So are Shirinoğlu Agha. We are asked to write our letters in Turkish by the government and therefore we are writing in Turkish. If you ask how we are doing, we are all doing fine, we earn a good living, the only problem we have is missing you. May God make us worthy to see each with our worldly eyes. Please greet our cousins Nazaret Ayjyan, Mardiros and Ohannes aghas. Here, your uncle Ohannes Agha and all his family members are fine. They send their greetings. All your neighbours here, both young and old, they are fine, and send their greetings. We hope that all of you there are doing well.

9 Teşrinisani 1333 R.

Mardiros Gchigyan

(P.S.) Մեր կողմէն հանգիստ եղէք։

Be assured that we are fine

Kevork Shamlian

This poignant reassurance that everybody is “fine” is a common theme throughout the Shamlian family letters. We see it over and over again as Kevork writes to his brother and son in America.

It was only then that I realized that these special greetings and the names mentioned referred to those who survived the first round of killings in their region, Arapgir. By the same token, this letter may well be the one that revealed those who might not be living anymore.

There is a reason this 1917 letter was written in Ottoman Turkish. After 1915, government scrutiny and censorship intensified. This was the last letter received from Shamlian family members—and most likely from many of those who sent their greetings.

Artin and Arkel, the recipients, were cousins, born and raised in Arapgir. They made a long and risky journey to the new country due to the insecurities, abusive and oppressive taxes they were unable to pay, and the danger of conscription and death in the old country before 1915. Oppression, impoverishment and death were already well-known to Ottoman Armenian subjects in the 19th century, long before 1915.

However, the most striking part is the fact that for years the Shamlians of Philadelphia assumed their family members had all perished in 1915. This letter proves otherwise. The family now wonders what their relatives endured in those two years from 1915 to 1917. Kevork was a weaver; perhaps his skills were needed by the authorities or the military.

The process of carefully reading and interpreting these letters has been labor-intensive, yet rewarding and enlightening. First and foremost, treating each and every letter as uniquely important by not hierarchizing them is liberating and empowering. We are not looking for a certain big incident or event. On the contrary, we are becoming more aware of the fact that we are witnessing the everydayness of violence, which levels layers of damage on the human soul, as well as an experience that culminated in a much bigger catastrophe—the genocide itself. Secondly, through transcription and translation, we follow the footprints and gain knowledge of lives eventually terminated. This offers a unique viewpoint not found in history books.

We are not looking for a certain big incident or event. On the contrary, we are becoming more aware of the fact that we are witnessing the everydayness of violence, which levels layers of damage on the human soul, as well as an experience that culminated in a much bigger catastrophe—the genocide itself.

Genocides do not only annihilate people and their cultural legacy. They erase the deep knowledge of local populations, including of the climate, soil, minerals and essential nature of that area. This knowledge had been accumulated over centuries, if not more. For our purposes, it is revealing to learn the day-to-day practices of Armenians in the provinces, especially of those who remained after sending their loved ones to faraway continents. The phenomenon of bantukhd, the Armenian migrant worker, had already been an issue by the mid-19th century, though America did not become a primary destination for Armenian workers en masse until the late 19th and turn of the 20th century.

The letters of the Shamlian family in Arapgir portray the randomness and embeddedness of inequalities, injustices and violence of everyday life. In 1913, Kevork Shamlian described his life in Arapgir as a “well of hell,” when hell had not yet broken out. Hence, these family archives open up a world in front of us—the world of Armenians of the provinces and the experiences of Armenian families before 1915. We witness their everyday lives, their longing for their loved ones and their desperation at being left behind.

On the other hand, the Shamlians’ letters give us glimpses into the high level of literacy among the Armenians of the provinces at the beginning of the 20th century. Among the letters we read, we encountered one written by a 21-year-old man from Arapgir to his father, blending classical Armenian forms with the local dialect—all expressed in wonderful handwriting.

We will continue to work on these documents and hope that research institutions around the world will consider supporting our work, given the importance revealed by this and other studies on family archives. As our experience shows, getting to know the moment when Armenians of the provinces turned into “angels of history,” in Walter Benjamin’s words—staring at the catastrophe they witnessed—is of utmost importance. Each moment of discovery releases and unhooks the past, granting a tiny piece of freedom—freedom for those already passed and freedom for the living who struggle to understand what happened to their ancestors.

Author information

The post “Be assured that we are all fine”: Letters from the ‘well of hell’ appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.