Groong (Crane)! Groong, what word do you have of home?

Le Le Yaman (Alas)! Le Le Yaman, our home, your home!

Oh, Groong, send word! Send word! Our homes are no more, our fields destroyed, our artwork and tombstones shattered, our books and churches burned. Our rivers flow red, and the now-barren countryside is filled with the dead and dying, while ragged, parched-lipped orphans with swollen bellies moan—begging for morsels of bread. With boney fingers they dig in the dirt, in the dung, for anything edible. Men are beheaded; boys and girls snatched. An old man here and an old woman there fall to the ground while a young mother lags behind the never-ending marches to where, no one knows. She kneels, carefully placing her lifeless infant on the ground, and with her emaciated hands digs a small grave. “So that my baby, light of my eye, will not be trampled,” she whispers to the earth, then to the heaven above, as she draws a small cross in the dirt. She does not weep, for her tears stopped flowing long ago. In response to the vile and hideous voices shouting, “Do you renounce…?” followed by “Do you accept…?” the voice of a nation cries out, “Hayr Mer… Our Father Who Art In Heaven…”, echoing still from the ashes of the churches and trampled bones buried by time.

Oh, Le Le Yaman—Our Nation! Send word!

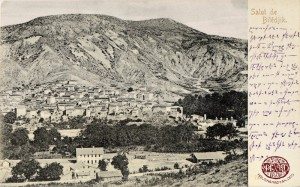

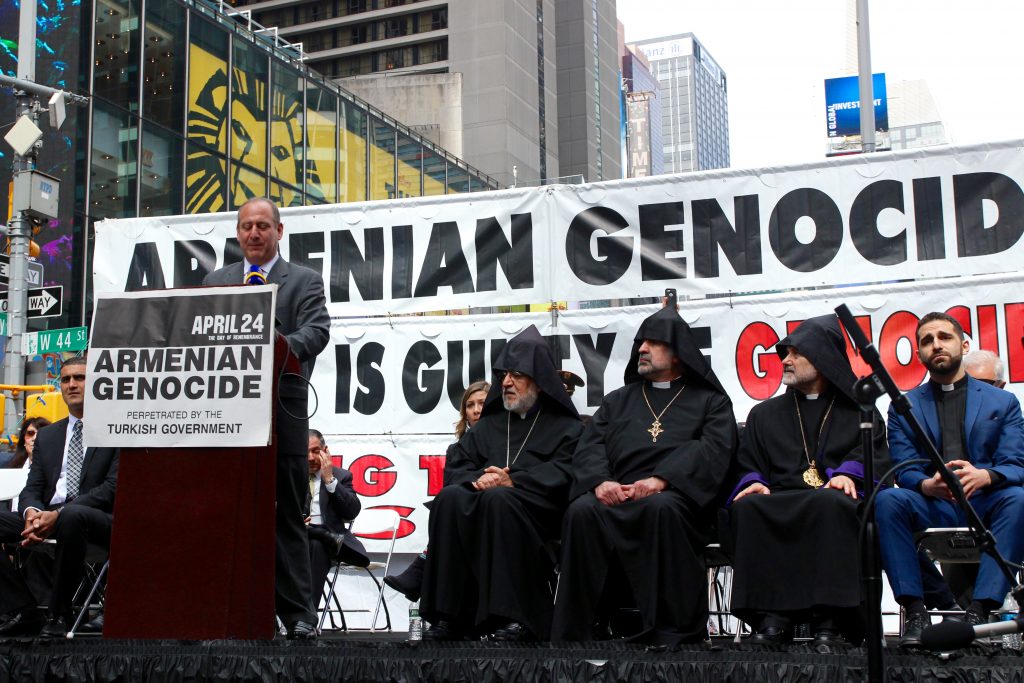

![]()

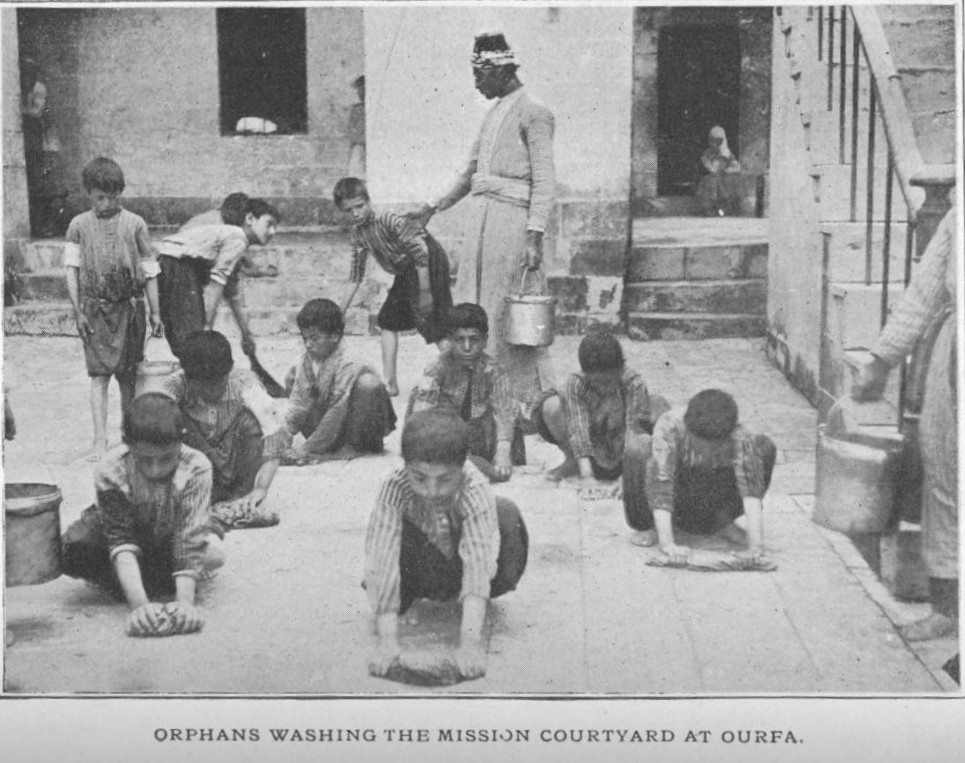

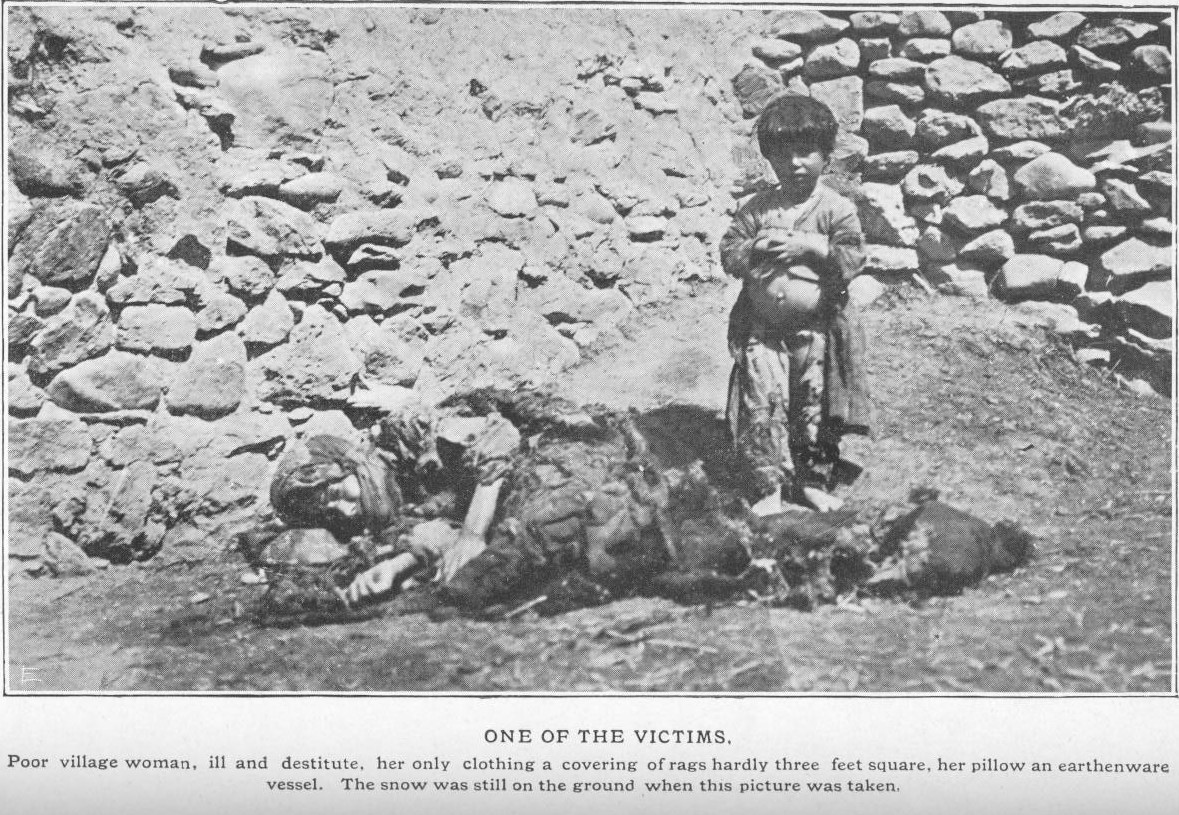

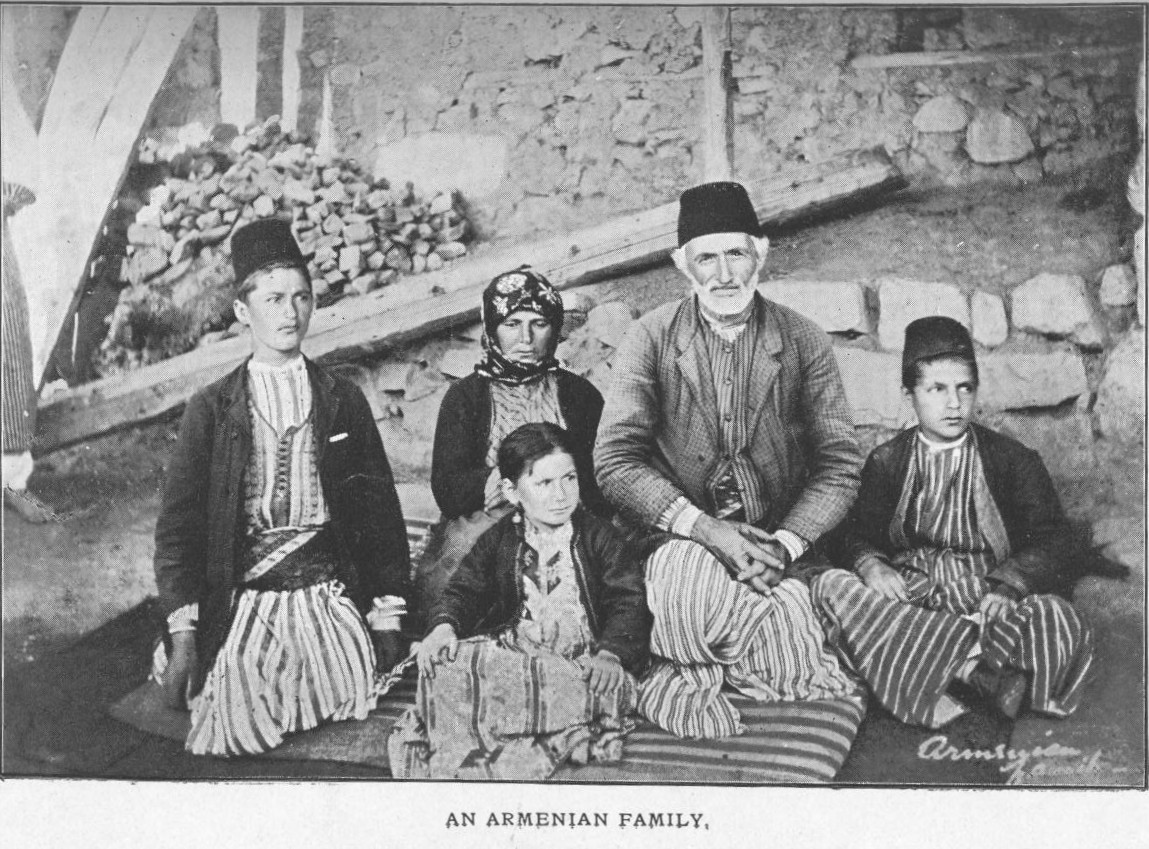

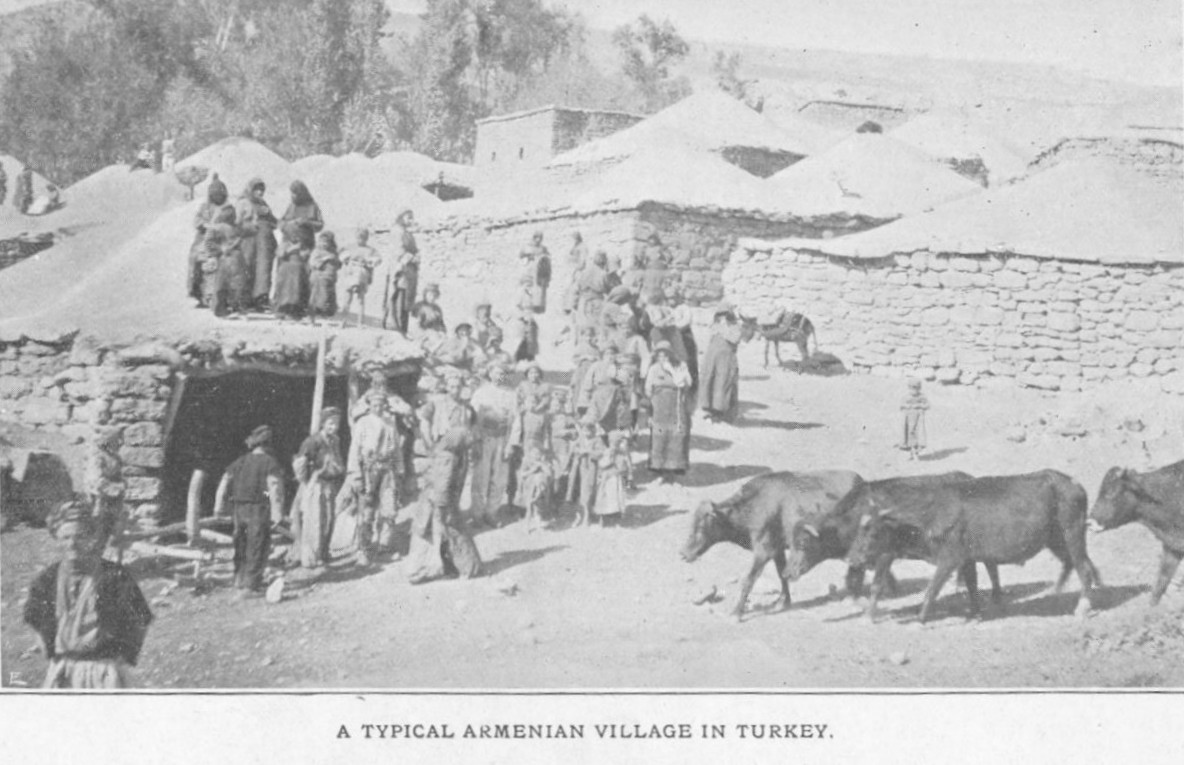

From J. Alston Campbell’s book, In The Shadow Of The Crescent

Amidst the unending dark clouds of tyranny and torture, plunder and massacre, some of the Armenian people, reduced to “a sea of suffering humanity,” somehow survived the 1915 genocide. A.E. Thompson, a missionary in Turkey, described the horrors in his piece published in New York on Oct. 16, 1915, in “The Alliance Weekly, A Journal of Christian Life and Missions” (Missionary Department), titled “Affairs in Turkey,” in these words:

“…the Turk has again let loose his forces of destruction that has made his name a byword…beginning in April with some local massacres and deportations, a campaign authorized by Constantinople and conducted by officials, army officers, and gendarmes, has become as wide as the far scattered Armenian population. It has varied in method and detail according to the character of the local authorities…the more humane officials have deported the Christian population… The brutal have massacred thousands, driven women and children in droves, not even permitting women in childbirth to halt by the way. Wholesale ravishing of women and horrible butchering of men are mere incidents. A conservative estimate puts the dead and dying at 500,000. Hundreds of thousands more will die of starvation in the hostile communities into which they are driven. The end is not yet. Their property is confiscated, and in many places, their homes are already in possession by Moslems… The Christian world winked at Abdul Hamid’s butcheries, and now it is powerless to prevent his successors, from whom so much was expected, from exterminating the thriftiest and cleverest of their subject nations…”

The following are a few more excerpts from the above publication, which included articles regarding the sufferings of the Armenians from the years 1909-19:

“October 23, 1915… The Christian world is again shocked by the new story of Armenian atrocities. Horrid cruelties are on a scale surpassing even the frightful wrongs of other years, which justified the title Mr. Gladstone gave to the Turkish ruler, ‘Abdul, the Assassin.’ … The present policy of the Turkish authorities, with the tacit support of their German allies, is the utter extermination of this sturdy and superior race…the entire destruction of the race.”

“October 30, 1915… The missionary work in Asia Minor, under the American Board, has been almost entirely wiped out. This brother, Dr. McNaughton, states that before the war there were 148 stations, 309 missionaries, 158 organized churches, 1,310 native helpers, 26,000 scholars in 450 schools and colleges, and 60,000 in attendance upon the missions. Today these flocks are scattered, and more than 1,000,000 Armenian Christians appear to have perished. Large funds have been sent from America by Armenian immigrants to bring their relatives to this country, but alas, the authorities have had to return the money, and report that the relatives could not be found. Is it the last drop in the full cup of Turkish crime…?”

“December 30, 1915… It has not been a conquered province that has suffered, but a subject nation, over which the Turks have ruled for centuries… Abdul Hamid shocked civilization by the massacres of a few thousand Armenians… He probably never conceived such horrors as the Young Turks, who dethroned him, have perpetrated. The report published by the Relief Committee states that out of a total Armenian population of 2,000,000 no less than 850,000 have died in the massacres or of disease, exhaustion, and starvation. A man who had been an eye-witness of much of the afflictions said that of the three causes of death, massacre, famine, and deportation, massacre was merciful and famine a boon in comparison to the sufferings of the deportations. The report of the Relief Committee reads: ‘Men were led away in groups outside their villages and killed with clubs and axes. The Consul of one of the European nations reported that on one occasion 10,000 Armenians were taken out in boats, batteries of artillery trained upon them, and the entire company killed. Girls and women were reserved for an indescribable fate in terrible marches; in harems, in the house of the officials, or in the tents of wild tribes. Villages and towns by the hundreds were wrecked. The whole Armenian population of large sections deported. Of 450 in one village only one woman lives. She saw her husband and three sons tied together and shot with one bullet and her daughters outraged and then killed. She was carried away by a Kurd but escaped by night, naked; and after terrible suffering fell in with some refugees. The blow fell heaviest upon the weakest—the aged, the women, especially the mothers and those about to become mothers.’ Read the most graphic pictures in prophecy of horrors and outrages and you have a mild picture of what has occurred.”

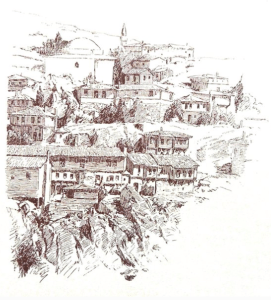

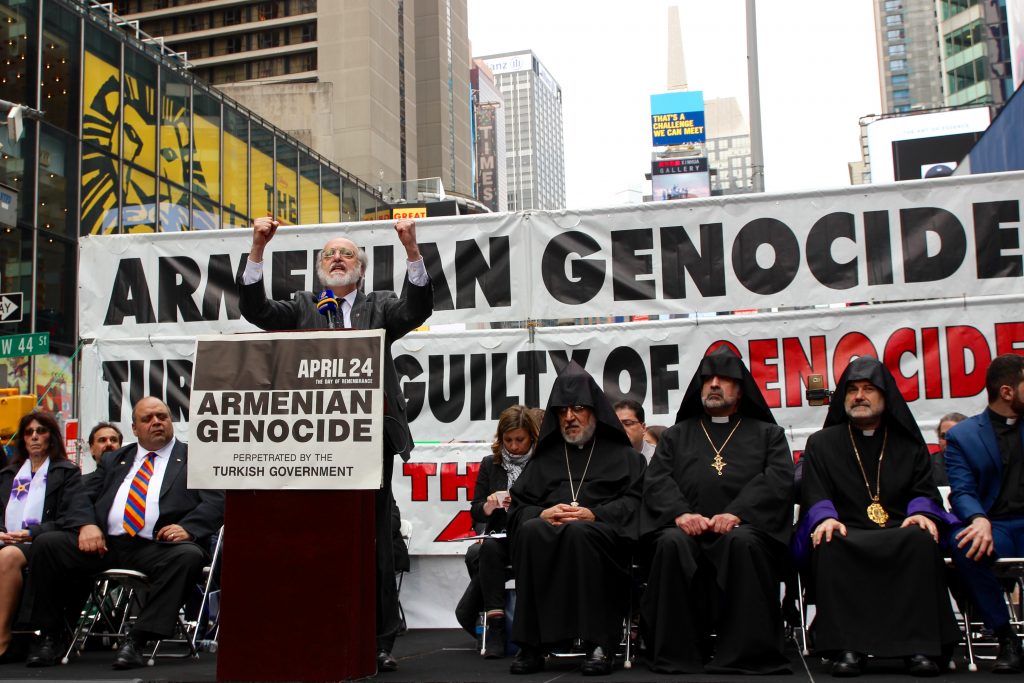

![]()

From J. Alston Campbell’s book, In The Shadow Of The Crescent

Numerous publications described the ordeals suffered by the Armenian people, among them Turkish Atrocities—Statements of American Missionaries on the Destruction of Christian Communities in Ottoman Turkey, 1915-1917 by James L. Barton; Days of Tragedy in Armenia—Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917 by Henry H. Riggs; Marsovan 1915: The Diaries of Bertha Morley by Bertha B. Morley; The German, the Turk and the Devil Made a Triple Alliance—Harpoot Diaries 1908-1917 by Tacy Atinkson; A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley by Ruth A. Parmelee; Shephard of Aintab by Alice Shepard Riggs; Diaries of a Danish Missionary—Harpoot, 1907-1919 by Maria Jacobsen; and The Tragedy of Bitlis by Grace H. Knapp.

Contemporary publications include The History of the Armenian Genocide (1995), German Responsibility in the Armenian Genocide (1996), and Warrant for Genocide (1999) by Professor Vahakn N. Dadrian.

To get an idea of the brutal life the Armenian suffered under Turkish tyranny, and Kurdish cruelty, and this before the 1915 Genocide, Deborah Alcock’s 1901 book titled, By Far Euphrates, and J. Alston Campbell’s 1906 book titled, In The Shadow Of The Crescent—both accounts of a people living daily in constant “dread of massacre and fear of the Turk”—offer the reader great insight. In William Watson’s 1896 book titled, The Purple East—A Series of Sonnets on England’s Desertion of Armenia, the author writes:

“The clinging children at their mother’s knee

Slain; and the sire and kindred one by one

Flayed or hewn piecemeal; and things name-

less done,

Not to be told: while imperturbably

The nations gaze, where Rhine unto the sea,

Where Seine and Danube, Thames and

Tiber run,

And where great armies glitter in the sun

And great kings rule, and man is boasted

Free!”

Alcock writes of her book:

“The greatest care has been taken to make the foregoing pages absolutely true to fact… Every instance given of martyrdom, properly so-called, or of courage, faith, patience, or devotion, is entirely authentic… The alteration of names was necessary…”

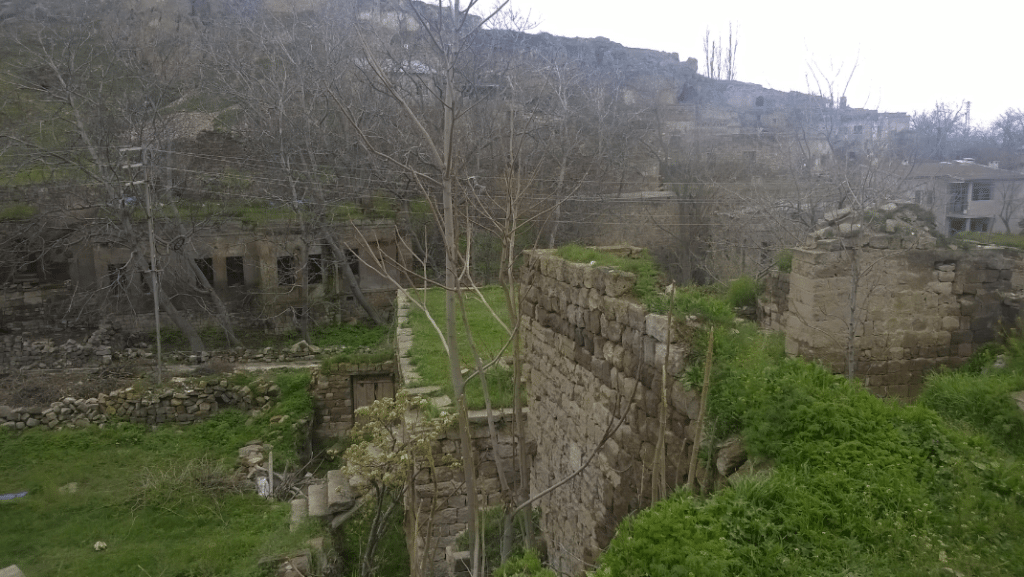

![]()

From J. Alston Campbell’s book, In The Shadow Of The Crescent

In the following passages, she writes:

“It was deliberate, organized, wholesale murder. First came the soldiers—Zaptiehs, Redifs, Hamidieh’s—then the Turks of all classes, especially the lowest, well furnished with guns and knives. Their little boys ran before them as scouts to unearth their prey. ‘Here, father, here’s another Giaour [Infidel]…’”

“… They clung together, the women and children weeping, the men for the most part silent in their terror. Above the sorrowful crowd rose a voice that said, ‘Let us die praying.’ Immediately all knelt down, and their hearts went up to heaven in that last prayer, which was not the cry of despair, but the voice of hope that, even then, could pierce beyond the grave…”

The Armenians had been pouring into their church to pray when the Turks set it on fire. After the iron doors of the church had been broken, the “work of the murder began in earnest.”

“… And now the Moslems had reached the altar. Some of them sprang upon it, while others tore the pictures, smashed the woodwork, and broke open anything they thought might contain treasure. There was on the reading-desk a large, beautiful, and very ancient Bible, bound and clasped with silver. With a yell of triumph, a Moslem seized it, tore out the leaves, and flung down, the desecrated volume. ‘Now, Prophet Jesus,’ he shouted, ‘save Thine own if Thou canst! Show Thyself stronger than Mahomet!”

“… The Turks meanwhile, were rushing up the gallery stairs, seizing the younger women and girls, and carrying them out. A Turk forced his way between Jack and Hanum Selferian, ‘Do you know me?’ he asked her, ‘I killed your husband yesterday. Come with me, and I will save you and your children.’ … The Armenian mother lifted her youngest child, a boy of eight, in her arms, and looked at the three little girls clinging to her side. “‘Children,’ she said, ‘will you go with that man and be Moslems, or will you die for Christ with me?’”

“‘Mother, we will die with you,’ said the little voices, speaking all at once.”

“She could do for them one thing yet. They should not suffer. In another moment they should be with Christ. Twenty feet down, right into the heart of the hottest fire, she flung her youngest child. Then followed the little girls; and then, just as the Turk’s hand touched her shoulder, her own rest was won…”

Campbell begins his book with an “Introductory Letter” from Dr. J. Rendel Harris:

“My dear Mr. Campbell, When I came upon you in the mission House in Aintab, having been on your trace at several points in Asiatic Turkey, you were just beginning to return into the sunshine from the Valley of the Shadow; the exposure to cold, the arduous labours in which you had been engaged, and the fever which always seem to be lurking in wait of the traveler, had so reduced you that it was doubtful if, after we left you, we should ever see you again… Probably there are not many English people who have seen so much of the inside of the Armenian trouble as Millard and yourself, and a lesser degree my wife and myself. Those who travel in great state, and under numerous escorts, see little or nothing of what is going on; they never escape from Turkish surveillance, and they never get near to Armenian confidence. Then they come home and write books, which glorify the persecutor and heap contempt on his victims… September 28, 1906.”

In his “Preface,” Campbell writes:

“Although not a few books have already been written on Asiatic Turkey, I am strongly of the opinion, for the following reasons, that there is room for this additional one. Hitherto the majority of those who have described this wonderful country and its people, have been either persons of title, scientists, scholars, or wealthy tourists, and these have not only written from their own standpoint, but by virtue of their position have received great attention from, and been more or less personally conducted by, the Turkish officials, who have endeavoured to keep from their view anything which it was not expedient for them to see. In my own case…I traversed the country as a plain ordinary man, and was usually regarded by the Turks as being an unimportant person who was not worthy of much notice, a fact which enabled me to mix more freely with the Christian race, to visit villages and districts away from the beaten track, and to see things as they really are. The information and incidents are not merely the impressions of a passing visitor, but may be taken as well-founded, for I have taken pains to confirm and verify…all that is recorded … When the story has been too horrible to relate in all its dramatic infamy, I have been compelled to draw a veil over certain things… Having no interest whatever in Asiatic Turkey of a commercial character, my chief object in writing this book has been to awaken the sympathies of the Christian nations of the West on behalf of a helpless and suffering people…”

In the following passages, Campbell, who knew and greatly admired the Patriarch Megerdich Khrimian for his humbleness and patriotism, and his people’s strong religious beliefs, writes:

“The Armenian priest, hoping, perhaps, to keep them (the Koords) from going to houses where there were girls in the family, took them to his own home and provided them with a good meal, setting before them the very best that could be provided from the scanty larders of himself and friends. When their appetites were satisfied, some of the food remained over. They then deliberately killed their host, and, after mixing his blood with this, took their departure…”

“… The thousands of Armenians who laid down their lives at the time of the massacres did not die on behalf of a political propaganda, they laid down for the Gospel, as a testimony to the Moslem world of the power of a living Christ. Most of those martyrs, had they wished, might have saved themselves by holding up one little finger as a sign that they accepted Islam. But they chose death rather than deny His Name, and their sentiments were well voiced by the old priest at Sassoun, who, when the Gospels he was in the habit of using in church were brought to him, and he was asked to curse them and live, replied: — ‘Do with me what you will, I cannot curse these symbols of our holy religion.’”

“… I stayed for several days in a village, and whilst in it saw an instance of the annoyance which is caused to the Armenians by the soldiery. A day or two after my arrival a party of foot soldiers entered the place. They had come from Moosh, and each one, before leaving that place had commandeered an Armenian, whom he compelled to carry his load without payment. When they reached the village, in which I was staying, these twenty or thirty soldiers, as is customary, compelled its inhabitants to feed them free of charge, ruthlessly killing the chickens of the poverty-stricken people, and the following morning, having devoured most of the eatables in the village, they employed themselves by hunting for a fresh batch of slaves to carry their loads to another town…”

“… Whilst passing through the dangerous gorge which leads from this plain to the town of Bitlis, Peter (an Armenian), who was walking ahead of our cavalcade, sought to pass on the narrow footpath through the snow, a Koordish lad, who, with his two Armenian servants, was proceeding in the same direction. ‘Don’t attempt to pass me,’ said the Koord, ‘you are an Armenian and must walk behind…’”

“Little regard is paid by Moslems to the honour of Armenian girls, who are sometimes stolen and at other times hunted like gazelles by their fiendish adversaries… In many Armenian villages scarcely a woman can be found who has not at some time or another been the forced victim of Koordish or Turkish lust…”

“The memory of previous massacres is still fresh in the minds of many, and the awful dread of having their loved ones torn from them to be hacked to pieces by the swords of the Turks, or to become the forced victims of Moslem passion, keeps these thousands of refugees from returning to their homes for a couple of days…the majority are obliged to sleep out in the open…”

“During the present year the Armenians in a certain little mountain village, almost beggars and without sufficient dry bread to satisfy their hunger, crouched in terror as they heard that the tax-gatherers were coming. The men looked with haggard eyes at their wives and daughters thinking of what might happen to them when the taxes were not forthcoming, and the women moved about with white, scared faces. Well might these peasants fear the approach of the officials, for in the villages below they had just tortured the people with fiendish barbarity. They had beaten the women and hung some of them up by the hair in order to beat them, then forced them to open their mouths to be spat into, and subjected them to unheard of indignities…”

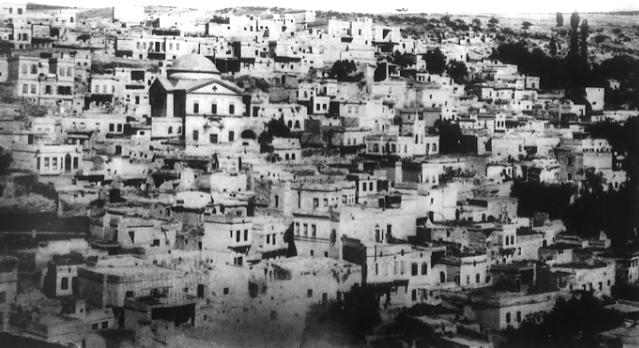

![]()

From J. Alston Campbell’s book, In The Shadow Of The Crescent

A hundred years have passed since that horrific period took place in the history of the Armenian people—April 24, 1915—and with it a hundred years of voices remembering, praying, commemorating, demanding justice for the wrongs committed. How, one wonders, has this small Christian nation survived and dealt with its immeasurable sufferings and losses? And, despite all they have gone through, how is it that they have prospered as individuals and as communities wherever they have gone?

Perhaps the answers lie in the people’s reverence for their church, language, heritage, and culture. Of the church, Campbell writes:

“The Armenian Church, during succeeding generations, has been called upon to pass through periods of the most terrible persecution, though her sons and daughters have always had to bear the full brunt of Moslem bitterness and oppression, and though she has repeatedly had to seal her witness with her blood, she still continues to uphold, amidst savagery and barbarism, the standard of the Cross…”

And, of the Armenian’s patriotism, he writes:

“…a strong feature in their character, and this, together with a wonderful recuperative power which they possess, has often enabled them to rise phoenix-like from disasters which would have ruined other nations.”

How then, after having commemorated this particular April 24, the Centennial, when His Holiness Karekin II and His Holiness Aram I presided together at the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin over a historic event—the canonization of the Martyrs who perished in the Armenian Genocide—can we, as individuals and as families, do our part in honoring the Martyrs and also the selfless men and women missionaries and individuals who risked, and at times sacrificed, their lives for the Armenian people?

The answer lies within each of us. Every time we enter our churches to pray and take part in our religious traditions; every time our children attend Armenian and or Sunday Schools and various Armenian youth activities; every time we, including our youth, attend Armenian community functions; every time we read a book or an Armenian newspaper to learn about our architecture, art, cuisine, culture, dance, history, language, literature, music, and religion, we not only honor the Martyrs, but we continue in their footsteps as Armenians.

“From the warm ashes of our ancient heroes

May there arise heirs worthy of them,

To give a new life to our people”

—Bechiktachelian

This article first appeared in the Armenian Relief Society international periodical “Hai Sird,” published in Oct. 2015 (issue number 160), on the occasion of the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide.

Credits

The Alliance Weekly—A Journal of Christian Life and Missions (Now called ALife),

Archives Department, Christian and Missionary Alliance, Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Alcock, Deborah, By Far Euphrates, London, 1901 (Elibron Classics, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation).

Campbell, J. Alston, In The Shadow Of The Crescent, London, 1906.

Watson, William, The Purple East—A Series of Sonnets on England’s Desertion of Armenia, London, 1896.

Hay Endanik, July-August 1973, Published by the Armenian Publishing House of the Mekhitarist Fathers, S. Lazzaro, Venice, Italy. (Beshigtashlian quote, page 46).